That is a mouthful.

The connection comes from Mary C Water's book, Ethnic Options: Choosing Identities in America. In her discussion of "symbolic" ethnicity she draws upon both deTocqueville (anticipating 102!) and William O. Beeman's analysis of advertising.

About deTocqueville she writes: "Tocqueville noticed that while individualism led people to find their own beliefs within themselves, this isolation was at the same time compatible with conformity, because people are constantly looking for affirmation of those beliefs in the people around them." (p. 148)

She quotes Beeman: "In the United States, through exercise of individual choice, people not only demonstrate their uniqueness, they also recognize and actualize their integration with others. They do this by making, acknowledging, and perpetuating ties based solely on the affinity that arises through making the same choices." (Waters, p. 150). Advertisers depend upon this combination of individualism and conformity when they offer us such things as blue jeans as a mode of self-expression and as a vehicle for demonstrating our membership in the group of people who wear that brand and style of jeans.

Thus, Waters argues that in the third and four generation after immigration, Americans select their ethnic identification in ways similar to selecting their cola preference: Pepsi, Coke, Royal Crown, etc. This sort of symbolic ethnicity does not require, or grow from, membership in an ethnic association or speaking the language or living in an enclave. It is as easy as wearing a Norwegian sweater to Christmas Festival at St. Olaf.

Another scheme for thinking about this comes from Willard B. Moore in the catalog for Circles of Tradition, an exhibit of folk art in Minnesota. He identifies three circles of tradition: integrated, perceived, and celebrated. In the first "forms, techniques, materials and symbolic meanings" are tightly integrated with community life. In the second, function either practical or symbolic, is primary. In the last, form is most important.

What struck me as I read Waters' conclusions was how closely they coincided with my recent post "Thanksgiving Jazz." She helped me to see that my observations about Thanksgiving might well be described with reference to this negotiation of individuality and conformity, this affinity based upon making the same choices.

conversing about and with America, Americans, and American Conversations students

Monday, November 29, 2010

Saturday, November 27, 2010

In class learning

Enich's Amcon Thoughts: Slave Justification:

I'm sure that every now and then students do learn something in the midst of class. In fact I have treasured memories of times I've watched the proverbial light-bulb click on as I have watched. It is an awesome sight. (I use the term in its original sense: that is, inspiring awe.) Moreover, this is a joy rare enough that I'm always grateful for it. So too, I'm grateful to Enich for this post to his blog which includes the news that he made a discovery in class. Thank you, Enich.

I'm also gratified that our efforts to think about slavery produced this specific learning: that American slavery did not appear full blown one afternoon in 1619 or even in the mid-1700s or the early 1800s. My hunch is that most Americans, regardless of our personal biological relationships to either slaves or slave owners, find our national history of slavery and its continued aftermath shameful, painful, and frightening enough that merely acknowledging the existence of slavery in "the land of the free" is hard enough. The topic sets us quivering with emotion and politics. To also take a careful, honest look at the large decisions and small compromises made by individuals, legislators, and institutions along the way to racialized, hereditary, life-time slavery is harder still.

Nonetheless, doing so is important not only for what we learn about the past, but also for what we learn about ourselves and our own potential for dramatic and banal evil. We need to be reminded of our ""perilous liberty." That is, our liberty is both"full of danger" and "exposed to imminent risk of disaster." The term is Jefferson's. Who better to serve as a warning to us about dangers of not paying attention to our scruples and about the importance of giving freedom a firm foundation in equality and justice.

see also post on The Grace of Silence

Definition of perilous from dictionary.com

I'm sure that every now and then students do learn something in the midst of class. In fact I have treasured memories of times I've watched the proverbial light-bulb click on as I have watched. It is an awesome sight. (I use the term in its original sense: that is, inspiring awe.) Moreover, this is a joy rare enough that I'm always grateful for it. So too, I'm grateful to Enich for this post to his blog which includes the news that he made a discovery in class. Thank you, Enich.

I'm also gratified that our efforts to think about slavery produced this specific learning: that American slavery did not appear full blown one afternoon in 1619 or even in the mid-1700s or the early 1800s. My hunch is that most Americans, regardless of our personal biological relationships to either slaves or slave owners, find our national history of slavery and its continued aftermath shameful, painful, and frightening enough that merely acknowledging the existence of slavery in "the land of the free" is hard enough. The topic sets us quivering with emotion and politics. To also take a careful, honest look at the large decisions and small compromises made by individuals, legislators, and institutions along the way to racialized, hereditary, life-time slavery is harder still.

Nonetheless, doing so is important not only for what we learn about the past, but also for what we learn about ourselves and our own potential for dramatic and banal evil. We need to be reminded of our ""perilous liberty." That is, our liberty is both"full of danger" and "exposed to imminent risk of disaster." The term is Jefferson's. Who better to serve as a warning to us about dangers of not paying attention to our scruples and about the importance of giving freedom a firm foundation in equality and justice.

see also post on The Grace of Silence

Definition of perilous from dictionary.com

BBC: "dense" objects

The British Museum and the BBC team up to tell the history of the world through a relatively few objects. (To be precise, through 100 objects at the start. Individuals have added more.) Their site says nothing about dense facts, but their approach will be familiar to students of American studies. Read an object, perhaps an ordinary one or perhaps a rare one; follow the story it unfolds to see what can be learned about the world it was a part of.

Unlike the probate lists we consulted in class or the dorm room inventories students prepared, these objects are selected rather than being everything one person or household or empire possessed The objects are selected from the museum's collection which suggests that a museum is, intentionally or not, a sort of time-capsule. The difference is that the makers and users of the objects did not set them aside for this purpose as we might when determining which things to put in a time capsule for 2010. (The Doc Marten's are an individual contribution, so intentional for a recent decade.)

BBC has broadcast all 100 episodes. (Among the more recent objects: a plastic credit-card. This would inevitably lead us to "The Graduate," to department stores, to identity theft, to bottled water, to recycling, and more.) The pod-casts are available along with photos of objects, a time-line, and other interesting stuff.

|

| Doc Marten Boots |

BBC has broadcast all 100 episodes. (Among the more recent objects: a plastic credit-card. This would inevitably lead us to "The Graduate," to department stores, to identity theft, to bottled water, to recycling, and more.) The pod-casts are available along with photos of objects, a time-line, and other interesting stuff.

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

Thanksgiving jazz

This year we did not have our customary AmCon 101, day-before-break, discussion of Thanksgiving. That topic allows us to tie together lots of themes from the semester: reading images such as paintings and cartoons of the "First Thanksgiving," the role of mythos and history in national identity, the importance of social location in memory, etc. We read about Plymouth Plantation and mid-20th century Native American protests. We talk about presidental declarations and the development of food practices. I missed the conversation. Last Sunday's Mpls StarTrib ran a feature about Thanksgiving illustrated by Rockwell's poster, "Freedom From Want." We could have talked about that as well.

As I've been planning for the dinner at our house tomorrow, I've also been thinking about how another American cultural practice might be a fine metaphor for the meal: jazz. There are certain usual, not quite mandatory, elements to this meal that function almost like the chord chart. Knowing that there will be turkey, stuffing/dressing, potatoes, bread, pie, etc. the cook's culinary imagination is set free to consider how to perform the meal this year. The turkey could be brined in green tea, or deep fat fried, or stuffed with something Italian, or coated in mayonnaise (I kid you not). What variations of cranberry sauce is always a compelling opportunity for me. This year there are three sorts: a pesto with lots of garlic, chutney with both fresh and dried pears (the later serendipitously supplied by guests last evening), and a sweeter one with red wine and spices! To shift the metaphor a bit, at least at our house, there are also old standards that won't be riffed upon: the bread dressing my husband's family loves and quarts of gravy for mashed potatoes.

Perhaps the brilliance and delight of Thanksgiving is not only that it gives us a channel to express gratitude, or that it is is vaguely religious in a capacious rather than sectarian way, or that it has not been moved to Monday, but that it affords Americans a salutary, creative opportunity to take comfort in the familiar and shared while also engaging in individual innovation.

|

| then there is the day after |

Perhaps the brilliance and delight of Thanksgiving is not only that it gives us a channel to express gratitude, or that it is is vaguely religious in a capacious rather than sectarian way, or that it has not been moved to Monday, but that it affords Americans a salutary, creative opportunity to take comfort in the familiar and shared while also engaging in individual innovation.

Tuesday, November 23, 2010

the smell of freedom

"Freedom smells of a freshly painted room,

of wooden floors swept with a willow broom,

and of stale raisin bread."

This from "Painting a Room" by Katia Kapovich

The poem itself is lovely and bittersweet as the contrasting smells of fresh paint and stale bread suggest. With an immigration visa in her pocket, the speaker is painting a room in preparation to leave. Gently the poem evokes the cost of freedom that is won by leaving behind or giving up.

of wooden floors swept with a willow broom,

and of stale raisin bread."

This from "Painting a Room" by Katia Kapovich

The poem itself is lovely and bittersweet as the contrasting smells of fresh paint and stale bread suggest. With an immigration visa in her pocket, the speaker is painting a room in preparation to leave. Gently the poem evokes the cost of freedom that is won by leaving behind or giving up.

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

Reading Buildings and other things

Structure of Stolaf Buildings: "After our discussion yesterday on the buildings of St. Olaf I thought about it more when walking around campus. The idea that the St. Olaf i..."

Katie kept thinking about Tostrud/Skogland after class and noted that mind, body, and spirit are all cultivated there, but added: "I think that these may have come together for function not as a result of major planning. It is nice and convenient I think and it does make a unique dynamic to the location but I feel like it may not have had a lot of intention."

She puts her finger on a larger interpretive issue that has come up in class more than once. Remember those Pocahontas paintings and our questions about what the artists intended for us to receive from their work? Volumes and volumes have been written on this topic; I won't solve it here. I do, however, want to make a small suggestion: the more angles of vision we can bring to bear, the richer and perhaps even more accurate will be our reading of a building, a painting, a poem, a political movement.

Are the multiple-uses of Skogland/Tostrud that address spirit and mind as well as body in an athletic facility MERELY a matter of convenience and function? How would we know? What are the limits of our interpretation?

Katie kept thinking about Tostrud/Skogland after class and noted that mind, body, and spirit are all cultivated there, but added: "I think that these may have come together for function not as a result of major planning. It is nice and convenient I think and it does make a unique dynamic to the location but I feel like it may not have had a lot of intention."

She puts her finger on a larger interpretive issue that has come up in class more than once. Remember those Pocahontas paintings and our questions about what the artists intended for us to receive from their work? Volumes and volumes have been written on this topic; I won't solve it here. I do, however, want to make a small suggestion: the more angles of vision we can bring to bear, the richer and perhaps even more accurate will be our reading of a building, a painting, a poem, a political movement.

Are the multiple-uses of Skogland/Tostrud that address spirit and mind as well as body in an athletic facility MERELY a matter of convenience and function? How would we know? What are the limits of our interpretation?

- Such an intention would be consistent with the college's official statements of its mission, so we can allow the possibility that this was a principled decision.

- The practice, i.e. multiple use buildings that serve spirit, mind, and body or some combination of at least two, is common at St. Olaf, so this might indeed be an institutional habit based in an expressed ideal. Indeed, we know that the previous gym (now the theater building) was also used for worship over several decades and that the current chapel building includes classrooms.

- Next, we should set off to the archives to look for documentary evidence. Did the planners of the buildings make any statements about their intentions? What was said at the ground breaking and dedication ceremonies? Of course, even if we don't find any explicit statements to the positive, unless we find statements in the negative, the possibility of a principled decision remains.

- Imagine the alternatives. If we had the opportunity to hold all classes somewhere other than in Skogland, would we? If we had the opportunity to hold large events such as Christmas festival somewhere else, would we? Are these temporary arrangements, consistent with official statements of mission, but not determined by mission?

- Do we need to divide the question a bit? Surely the classrooms are there "on purpose" even if use of the gym for ceremonial events is in part due to lack of an alternative. Does this lead us to modify the interpretation so that the intentions of the builders is less central and defensible interpretation by the users is the primary concern?

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

Buying Identity

"To put it another way, consumption is a quest for identity through sensual means. We buy what we think we see in a object, grasping at the physical to get at the intangible, buying the commodity to obtain the unsaleable quality." Dell Upton, An American Icon," in Architecture in the United States.

This is the best definition of consumption, or consumerism, that I have read. Upton makes visible the illusive desire that drives us when we buy stuff, but are really searching for what stuff can not provide. By doing this Upton also allows the reality that we do need, or at least make use of, some of that stuff for practical purposes. I need a coat to keep me warm and footwear to keep my feet dry. The utility of those items is one crucial aspect of why I select this coat, not that one; these boots, not those boots. Like a building, both coat and boots also have "firmness" that makes them suitable to this climate and durable through the whole winter season, even into the next and the ones after. Third, winter gear might also have "beauty." But here is where we get out on thin ice. If I prefer a red coat and leather boots, if the lines of this coat flatter me and those boots suggest my Scandinavian heritage, have I moved beyond the pleasure of beautiful, useful clothing into consumption? Have my red coat and leather boots become part of my "quest for identity through sensual means" even if they continue to fulfill their tangible, physical task?

|

| No, that is not me, but . . .maybe if . . |

Habits of famous people

In his pockets, Jefferson carried such a variety of portable instruments for making observations and measurements that he's been dubbed a "traveling calculator." Among his collection of pocket-sized devices were scales, drawing instruments, a thermometer, a surveying compass, a level, and even a globe. To record all these measurements, Jefferson carried a small ivory notebook (pictured) on which he could write in pencil. Back in his Cabinet, or office, he later copied the information into any of seven books in which he kept records about his garden, farms, finances, and other concerns; he then erased the writing in the ivory notebook. This about Jefferson from Monticello.org

Even as Franklin's system of self-examination and cultivation of virtues reminds one of the the flurry of i-phone apps for self-improvement, Jefferson's habit of recording all sorts of information seems familiar. In his pocket he carried a small note-book for temporary jotting. Later in the day he transferred information to his commonplace books. This may have been analogous to tweeting to himself. Perhaps the point is less the specific system and more the habits of noticing and reflecting that these men's peculiar systems support. Keeping a journal, as many Protestants did to record their spiritual state, or even being forced by one's teachers to write a blog about a class are similar systems also intended to develop and support habits of noticing and reflection upon the world and our place in it.

Even as Franklin's system of self-examination and cultivation of virtues reminds one of the the flurry of i-phone apps for self-improvement, Jefferson's habit of recording all sorts of information seems familiar. In his pocket he carried a small note-book for temporary jotting. Later in the day he transferred information to his commonplace books. This may have been analogous to tweeting to himself. Perhaps the point is less the specific system and more the habits of noticing and reflecting that these men's peculiar systems support. Keeping a journal, as many Protestants did to record their spiritual state, or even being forced by one's teachers to write a blog about a class are similar systems also intended to develop and support habits of noticing and reflection upon the world and our place in it.

Freedom in the Airports

Freedom in the Airports: " On Saturday a man from Oceanside, CA was thrown out of the San Diego International Airport because he refused to submit to a full body ..."

Thanks Megan for this response to last weekend's incident. (Also for the fabulous Play Mobile image!) What a story this is! This man's refusal of a full-body scan is a fine illustration of the relative value given to security (freedom from fear) and other sorts of freedom.

Every time I stand in that long line, shoes off, 3-1-1 bag in hand, i.d. clenched in my teeth, I think, "For centuries human beings dreamed that being able to fly would make them free." Not.

|

| MSP security line: I've been there. |

Every time I stand in that long line, shoes off, 3-1-1 bag in hand, i.d. clenched in my teeth, I think, "For centuries human beings dreamed that being able to fly would make them free." Not.

Sunday, November 14, 2010

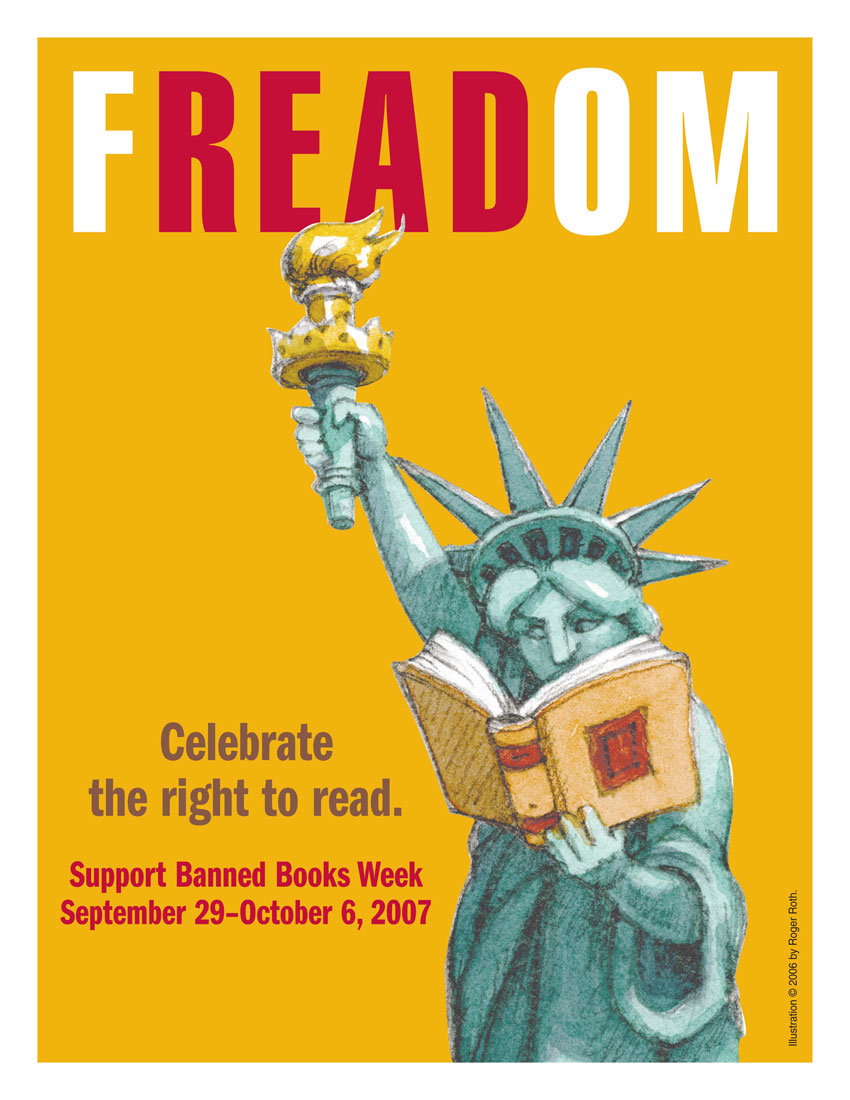

Freedom to read

ALA | Banned Books Week

Sorry to have missed the actual week for this. Need I say more?

Anne Hutchinson read the Bible; Benjamin Franklin printed books; Thomas Jefferson sold his library to Congress.

Not only freedom of the press to print, but also our freedom (responsibility) to read are necessary for our informed participation as citizens.

(Notice, the conflation of freedom and right on the poster.)

Sorry to have missed the actual week for this. Need I say more?

Anne Hutchinson read the Bible; Benjamin Franklin printed books; Thomas Jefferson sold his library to Congress.

Not only freedom of the press to print, but also our freedom (responsibility) to read are necessary for our informed participation as citizens.

(Notice, the conflation of freedom and right on the poster.)

The New Beauty: Sustainability

The New Beauty: Sustainability: "'The default setting of our civilization needs to be reset to ensure that we build a sustainable world that is also spiritually sustaining. ..."

Commenting on David Orr, Marissa wrote: "I have never thought about sustainability this way: ensuring beauty for the future. Brilliant!"

Thanks Marissa. Now I need to scroll down to find the post I wrote about Terry Tempest Williams and her assertion that beauty is not optional. This seems especially significant in view of those three approaches to reading buildings, the third of which asks about its beauty.

Let's keep noticing the attention and value authors and activists give to beauty. Jonathan Edwards cared for it, but I wonder how often American Christians of various sorts have given any sustained, thoughtful consideration to beauty. And what about politicians: are they willing to fund projects that include a line-item for beauty? Yes, there are some provisions for "public art." Nonetheless, I suspect that beauty is often relegated to the category of values that are expendable. We Americans most often value function over form.

Is anyone willing to assert freedom from ugliness as important for the common good? Was something like that behind Jefferson's careful design for UVA?

Commenting on David Orr, Marissa wrote: "I have never thought about sustainability this way: ensuring beauty for the future. Brilliant!"

Thanks Marissa. Now I need to scroll down to find the post I wrote about Terry Tempest Williams and her assertion that beauty is not optional. This seems especially significant in view of those three approaches to reading buildings, the third of which asks about its beauty.

Let's keep noticing the attention and value authors and activists give to beauty. Jonathan Edwards cared for it, but I wonder how often American Christians of various sorts have given any sustained, thoughtful consideration to beauty. And what about politicians: are they willing to fund projects that include a line-item for beauty? Yes, there are some provisions for "public art." Nonetheless, I suspect that beauty is often relegated to the category of values that are expendable. We Americans most often value function over form.

Is anyone willing to assert freedom from ugliness as important for the common good? Was something like that behind Jefferson's careful design for UVA?

"It's not a revolution if . . . ."

One of those NPR moments: driving home from school this afternoon I heard part of a story about changes in technology. Of course I didn't catch the name of the author being interviewed. Nonetheless, this statement doesn't need either the author's name or the precise context to be thought provoking.

"It is not a revolution if there aren't any losers." Is this true? Are there always losers in a revolution? Not much reflection was needed for me to begin to think that this probably is true and to be rather taken aback that I so seldom think about this reality. Perhaps the aura of triumph and patriotic pride that surrounds our American Revolution leads us--me--to focus upon the happy outcome that our nation came into being, the first nation founded on a good idea.

Certainly the British lost the war, but I wonder how much they cared. That is a question someone must have written about. In these last few days we have been reading some authors who pointed out that the Revolutionary promise of freedom was a long time in fulfillment for many types of Americans; those Americans might be construed as losers in some sense.

If the tea party movement is pushing us toward some sort of revolution in governance, we'd do well to consider who will lose in the changes.

"It is not a revolution if there aren't any losers." Is this true? Are there always losers in a revolution? Not much reflection was needed for me to begin to think that this probably is true and to be rather taken aback that I so seldom think about this reality. Perhaps the aura of triumph and patriotic pride that surrounds our American Revolution leads us--me--to focus upon the happy outcome that our nation came into being, the first nation founded on a good idea.

Certainly the British lost the war, but I wonder how much they cared. That is a question someone must have written about. In these last few days we have been reading some authors who pointed out that the Revolutionary promise of freedom was a long time in fulfillment for many types of Americans; those Americans might be construed as losers in some sense.

If the tea party movement is pushing us toward some sort of revolution in governance, we'd do well to consider who will lose in the changes.

Saturday, November 13, 2010

pop culture and the declaration

Cullen says that the Revolution is not of immediate interest to many Americans. This disinterest is in contrast to our irritated interest in the Puritans and uncomfortable awareness that the issues of the Civil War are not settled. Cullen suggests that contemporary Americans are still interested in the Declaration of Independence. I'm sure he is pointing to its ideals more than to the document itself as an artifact. And yet there is the movie, "American Treasure." It is fun and fast paced and plunges viewers into arcane details of the Revolutionary era. It makes me laugh out loud. It almost convinces me to like Nicholas Cage. Of all the bits and pieces in the movie, I like Ben Franklin's glasses the best. Sure, this is partially because I have bifocals, but it is also because the notion that Franklin manipulates how we see so many decades after his death seems in character. I think he would have been pleased as well as amused.

Cullen says that the Revolution is not of immediate interest to many Americans. This disinterest is in contrast to our irritated interest in the Puritans and uncomfortable awareness that the issues of the Civil War are not settled. Cullen suggests that contemporary Americans are still interested in the Declaration of Independence. I'm sure he is pointing to its ideals more than to the document itself as an artifact. And yet there is the movie, "American Treasure." It is fun and fast paced and plunges viewers into arcane details of the Revolutionary era. It makes me laugh out loud. It almost convinces me to like Nicholas Cage. Of all the bits and pieces in the movie, I like Ben Franklin's glasses the best. Sure, this is partially because I have bifocals, but it is also because the notion that Franklin manipulates how we see so many decades after his death seems in character. I think he would have been pleased as well as amused.

Friday, November 12, 2010

books

What is the difference between Thomas Jefferson's love of books and contemporary infatuation with digital connectivity? At least one significance difference that matters a great deal in my experience is this: each book I hold in my hand is a distinct encounter with the material world. I have a sensory experience of the book that includes how it appears to my eyes (color, size, shape, design and more), how it feels in my hands (size, weight, texture, etc.) , its aroma. Even it the author is not in the room with me, the book imposes the reality that its author is a person and its ideas are embodied.

When I provide access to readings via a PDF, I mourn the opportunity to hold the book or journal in one's hands and the possibility that touching the paper will be a channel of interaction with the author as well as a transfer of information. While I don't want to minimize the power of imagination which can transport one from 21st century Minnesota to 1st century Greece or 19th century India via a book or a on-line text, I also know that being in 21st century Greece with one's foot on the old Roman Road or in 21st century India surrounded by the aroma of jasmine stimulates the imagination and facilitates time travel.

When I provide access to readings via a PDF, I mourn the opportunity to hold the book or journal in one's hands and the possibility that touching the paper will be a channel of interaction with the author as well as a transfer of information. While I don't want to minimize the power of imagination which can transport one from 21st century Minnesota to 1st century Greece or 19th century India via a book or a on-line text, I also know that being in 21st century Greece with one's foot on the old Roman Road or in 21st century India surrounded by the aroma of jasmine stimulates the imagination and facilitates time travel.

Thursday, November 11, 2010

buildings: reading, writing, interpreting

Vitruvius, via Barnet, urges us to consider three aspects of buildings:

In his discussion, he offers examples that point to the symbolic function of buildings, or to their meaning, which is related to but not quite the same thing as their function. Of course some buildings are intended to make a statement, while others just do so because human beings are seekers of meaning and we will make meaning out of whatever materials are available.

While these three factors all assume human action in design, construction, and use, the people who use the building are not Barnet's primary concern. Some buildings are no longer in ordinary use, but most buildings were constructed with the expectation that they would be used. I"m curious about how our reading of a building might also contribute to our understanding of the communities that use them. More specifically, could we use the same three foci to consider a community?

All of this calls to mind the work of St. Olaf faculty member Mary Griep. In her current body of work,

ANASTYLOSIS PROJECT, she re-presents 12th century sacred buildings from around the world. Rather than writing about them, she constructs scale drawings that also incorporate techniques such as collage. Of course she can not include an American building in this project, nonetheless, her work provides an inspiring example of paying close attention to the details as well as to the whole. Each drawing highlights the beauty of the building and suggests its meaning.

- function or utility

- firmness or structural soundness

- beauty or design

In his discussion, he offers examples that point to the symbolic function of buildings, or to their meaning, which is related to but not quite the same thing as their function. Of course some buildings are intended to make a statement, while others just do so because human beings are seekers of meaning and we will make meaning out of whatever materials are available.

While these three factors all assume human action in design, construction, and use, the people who use the building are not Barnet's primary concern. Some buildings are no longer in ordinary use, but most buildings were constructed with the expectation that they would be used. I"m curious about how our reading of a building might also contribute to our understanding of the communities that use them. More specifically, could we use the same three foci to consider a community?

- What is the community's reason for being? What is its purpose?

- How sound is its structure, organization, and institutions?

- What beauty or delight does the community generate? What good does it offer?

All of this calls to mind the work of St. Olaf faculty member Mary Griep. In her current body of work,

ANASTYLOSIS PROJECT, she re-presents 12th century sacred buildings from around the world. Rather than writing about them, she constructs scale drawings that also incorporate techniques such as collage. Of course she can not include an American building in this project, nonetheless, her work provides an inspiring example of paying close attention to the details as well as to the whole. Each drawing highlights the beauty of the building and suggests its meaning.

Tuesday, November 9, 2010

Sara Miles (not Benjamin Franklin): freedom from want

This evening Sara Miles read from her books Take This Bread and Jesus Freak in St Olaf's Viking Theater. She told the story of her "coming late to Christianity" by means of being fed at St. Gregory of Nyssa church in San Francisco and of her continuing conversion while founding and overseeing a food pantry (video) where 600 families are given groceries every week. She convinced the leaders of the parish to try the project by quoting the passage from Luke inscribed on their altar: He ate with sinners. She tells this as a story about Christianity and the church. Certainly it is that. Surely there is much to learn from her assertion that a spiritual life is also a physical life.

I'm intrigued by what she says about church, but I also listened with AmCon ears and was struck by the degree to which her story is the opposite of Franklin's story. Rather than offering sage little proverbs about how to get ahead and recounting contributions to the common good as Franklin did, Miles simply described her experience of receiving abundant grace in a piece of bread and being compelled to give away food. Can this be an American story? Could we recognize our abundance as a charter for generosity? Could the dream be for a "better, richer life" for everyone, not just for anyone who wants it badly enough, and works hard enough, or is lucky enough?

Perhaps the way to insure freedom from want is to share.

Here's testimony from another woman who thinks it. From NPR's This I Believe Series: The Art of Being a Neighbor by Eve Birch

I'm intrigued by what she says about church, but I also listened with AmCon ears and was struck by the degree to which her story is the opposite of Franklin's story. Rather than offering sage little proverbs about how to get ahead and recounting contributions to the common good as Franklin did, Miles simply described her experience of receiving abundant grace in a piece of bread and being compelled to give away food. Can this be an American story? Could we recognize our abundance as a charter for generosity? Could the dream be for a "better, richer life" for everyone, not just for anyone who wants it badly enough, and works hard enough, or is lucky enough?

Perhaps the way to insure freedom from want is to share.

Here's testimony from another woman who thinks it. From NPR's This I Believe Series: The Art of Being a Neighbor by Eve Birch

Monday, November 8, 2010

automobiles and freedom

dodge challenger ad

"Two things America got right: cars and freedom."

First responses:

p.s. thanks to Evan who posted this.

"Two things America got right: cars and freedom."

First responses:

- We have long associated the first with the second.

- Having a car is a symbol of and a tool for freedom that far exceeds mere transportation or mobility.

- The Eisenhower interstate highway system was built to insure national security, but ends up being used for cars that allow us to go on vacation and to have houses a long way from our employment.

- But, that also limits the time we spend at home and forces us to spend time in traffic, if we have cars and jobs and houses in the suburbs.

- Not to mention our "enslavement" to those who have the oil needed to fuel the cars.

p.s. thanks to Evan who posted this.

Picture Blog 4 : The Puritans

Will's Commonplace Blog: Picture Blog 4 : The Puritans: "The Puritans & The New World"

Thanks to Will for taking the scrap-book-y aspect of a common-place book to heart! I love the images he has posted for various (dense fact) topics we're considered so far. Follow the link to this one and then enjoy the others as well.

I picked this one because it shows us that someone thought that a picture of a Puritan in a big hat would help sell something. What? We've read R. Greene on use of images of Indian women to sell tobacco and other products. That makes sense. Indians were associated with tobacco. Images of indian women had both positive and negative symbolic power. What, I wonder, is the symbolic power of this Puritan?

Thanks to Will for taking the scrap-book-y aspect of a common-place book to heart! I love the images he has posted for various (dense fact) topics we're considered so far. Follow the link to this one and then enjoy the others as well.

I picked this one because it shows us that someone thought that a picture of a Puritan in a big hat would help sell something. What? We've read R. Greene on use of images of Indian women to sell tobacco and other products. That makes sense. Indians were associated with tobacco. Images of indian women had both positive and negative symbolic power. What, I wonder, is the symbolic power of this Puritan?

Sunday, November 7, 2010

Freedom had or longed for

The most striking point J. Cullen makes in his chapter on the Declaration of Independence is his assertion that before the Declaration and the Revolution, freedom was something free, Englishmen in the colonies had and after that freedom became something they and others dreamed of having. Before, it was something to be preserved; after, it was something longed for, even fought for.

This suggests that American freedom is a bit like faith as presented in the epistle to the Hebrews: the assurance of things unseen. Indeed, the distance between American ideals and American reality is the space in which the dream exists, but only if there is an expectation that the gap can be closed. If America is predicated on a dream, or on having a dream, the eschatology is always marked by longing rather than fulfillment

Perpetual change is hardwired into our expectations and our rhetoric.

This suggests that American freedom is a bit like faith as presented in the epistle to the Hebrews: the assurance of things unseen. Indeed, the distance between American ideals and American reality is the space in which the dream exists, but only if there is an expectation that the gap can be closed. If America is predicated on a dream, or on having a dream, the eschatology is always marked by longing rather than fulfillment

Perpetual change is hardwired into our expectations and our rhetoric.

process: strategic planning and revolution

Friday evening and most of Saturday I spent at my congregation engaged in strategic planning. Anyone who has been involved in such an exercise in the past years would recognize the steps, the jargon, the big-paper-on-the wall, post-its, markers, and colored dots for "voting." All of this is intended as a method to direct lots of people's energy and ideas toward some larger purpose while generating their "buy in." I've done it before; I've even been the one asking folks to do it.

But this time I was doing it while also thinking about the American Revolution and that led me to think some new things:

But this time I was doing it while also thinking about the American Revolution and that led me to think some new things:

- There is an implicit theory of revelation at work. At least in a church setting, the unstated assumption is that by following this process a group of 50 people (in our case) will happen upon a true understanding of God's intentions for them and their congregation. We prayed a little. We did not read the Bible. We trusted that the Spirit would speak through us and our process. Could be, but it is a novel sort of discernment process.

- My hunch is that this is more a democratic expectation than a Christian one. That is to say, the process was not developed as a spiritual practice, but out of a democratic view of of governance and planning that expects that a bunch of people conferring together will arrive at wise decisions about what is good for them and others.

- I wondered if I could write a satirical sketch about the Committee of Five and the Continental Congress as they worked their way through SWOT analysis, drafting a mission statement, waiting for the Pennsylvania delegation to get approval from home of that draft, moving on to vision statements, and then proposing action steps. Imagine the excitement if we could find some post-it-notes written by Samuel Adams!

Friday, November 5, 2010

Tea party -- then and now

Thanks to Dan for pointing out this NPR story that takes up the symbolic and historical connections between the contemporary tea party movement and the pre-Revolutionary destruction of tea by an unruly group of Bostonians mildly disguised as Mohawks. While this is hardly a new insight, I'm reminding while reading that history often is transformed into mythos. When it is, the power of the story is less in the accuracy of the details than in the way it inspires imagination and action.

Thursday, November 4, 2010

getting a life in the midst of stuff and on this earth

If a dense fact approach is used in the hope of perceiving new dimensions of depth, as I think it is, then our local 'guru' of the dense fact has demonstrated the value of the approach in his newly released, much anticipated book: The Nature of College. While I could go on and on about it, far better for you to take a look yourself! Here is the book's own page: LINK. Keep a look out for the facebook pages for this book and for its major characters: Joe and Jo, siblings attending two different colleges.

feet of clay

When I used the idiom, "feet of clay," in class yesterday I got back looks of incomprehension. I could easily say that the idiom indicates that a person is not as good as one might have thought, but I did not know the origin of the phrase. Here it is: Daniel 2: 34. The reference is to a statue made of metals, but whose feet are clay and easily broken. So, the phrase indicates a hidden flaw that weakens the figure.

Wednesday, November 3, 2010

questions from the fork-less people

|

| forks are a sign of class in probate lists from the colonial period |

Great questions from today's discussion in section A where we considered the revolution from the perspective of people who owned few if any forks or who were required to polish other people's forks and may have longed for something to eat, with or without forks.

Next week we'll turn to the Declaration of Independence. I'm looking forward to reading it with these questions in mind. These are not precisely the questions Jefferson, Franklin, and Adams were addressing, but neither are these questions irrelevant to what they wrote.

the other hot beverage: Coffee Party

LINK

Here's what they say about themselves: "As we enter our eighth month, the Coffee Party's long-term focus is to develop, replicate, and sustain an effective method of engagement. We are creating models of participation based on responsible citizenship — a sense of civic duty, patriotism, and a respect for our democratic system of government. Our goal is an informed and involved electorate that takes seriously the responsibilities of citizenship, not only for the purpose of winning elections, but to effectively govern our nation on behalf of The People, and no other interest."More later on this. For now, and being a bit silly, I wonder if a hot chocolate party is next?

Tuesday, November 2, 2010

getting a life

Yet one more that connects with Franklin, but not only to him. We put Franklin in a section titled "The Good Life in America" that is our run up to the Declaration of Independence and all of this is part of our larger, semester long attention to freedom. So, we could say that the whole term is about "getting a life." But, the question, always remains, which one is the life one wants to get? [Here I should go find a Billy Collins poem. When I get it, I'll link it.] What is that dream that America offers and Americans long for?

At. St. Olaf we've come to talk about this a lot in terms of vocation. Why? Well, you can point to the money the Lilly Endowment gave out to a bunch of schools for "theological reflection on vocation." We got some of that, so we were obligated to think about vocation. But, before there was money in it, and after the money is gone, we also have the treasure of Lutheran teaching on the topic of vocation. This is not what Paul Dovre has called vocation-lite. Rather this is vocation that comes from outside the hearer; a calling that calls one out of the easy places to significant, response-ability, consist with God's gracious intentions for the world: justice, mercy, abundant life for all. Perhaps the voice will be directly God's, but it may as often be the voice of the neighbor that calls. This is a calling that anticipates response, even obedience.

Here David Brooks, a political observer, gives us another take on such a life,using different vocabulary: the summoned self. Link I'm reminded of Annie Dillard's essay, Living Like a Weasel, in which she write about the "perfect freedom of a single necessity." Perhaps this a more generalized expression of what the Puritans and Anne Hutchinson were looking for. They anticipated the "perfect freedom" of obedience to God. This is a sort of autonomy, unconstrained moral freedom, even when the barriers are many and strong.

At. St. Olaf we've come to talk about this a lot in terms of vocation. Why? Well, you can point to the money the Lilly Endowment gave out to a bunch of schools for "theological reflection on vocation." We got some of that, so we were obligated to think about vocation. But, before there was money in it, and after the money is gone, we also have the treasure of Lutheran teaching on the topic of vocation. This is not what Paul Dovre has called vocation-lite. Rather this is vocation that comes from outside the hearer; a calling that calls one out of the easy places to significant, response-ability, consist with God's gracious intentions for the world: justice, mercy, abundant life for all. Perhaps the voice will be directly God's, but it may as often be the voice of the neighbor that calls. This is a calling that anticipates response, even obedience.

Here David Brooks, a political observer, gives us another take on such a life,using different vocabulary: the summoned self. Link I'm reminded of Annie Dillard's essay, Living Like a Weasel, in which she write about the "perfect freedom of a single necessity." Perhaps this a more generalized expression of what the Puritans and Anne Hutchinson were looking for. They anticipated the "perfect freedom" of obedience to God. This is a sort of autonomy, unconstrained moral freedom, even when the barriers are many and strong.

dense facts and lizard eyes

"INQUIRERS IN AMERICAN CULTURE STUDIES SHOULD NOT LOOK FOR FACTS IN EXPERIENCE, BUT FOR "DENSE" FACTS—facts which both reveal deeper meanings inside themselves, and point outward to other facts, other ideas, other meanings.. . ." from Gene Wise, "Some Elementary Axioms for an American Culture Studies" Prospects (1979), 4: 517-547 Cambridge University Press via Jay M "Some [New] Elementary Axioms for an American Cultur[al] Studies" AMerican Studies 1997, vol 38, n. 2, pp. 9- LINKED

At St. Olaf we think of Jim Farrell (see his new book: The Nature of College) as the king of the dense fact, perhaps even as the originator of this approach. In fact, it is an American Studies approach which appears to have been suggested by Gene Wise in 1979. Recently I gained some new perspective on the dense fact approach and disciplinary study when I heard from two remarkable scholars at the 2010 American Academy of Religion meetings in Atlanta.

First: Richard Carp spoke to a workshop on interdisciplinarity. As I've come to expect from him, he brought clarity to the complex matter without over simplification.

Terminology: mutlidisciplinary is like parallel play. Two or more disciplines are in play, but not with each other. I (DeAne) think of this a bit like a meal served in courses. Interdisciplinary requires that two or more disciplines are working together. I suppose this might be like using two chop-sticks rather than a spoon which is set down and then a fork. Transdisciplinary, is applied to a topic or subject of study that requires more than one discipline to consider. Food, in my view, is a fine example of such a topic. A dense fact needs to be such a topic.

Richard also spoke of these matters by analogy to sight, more specifically to the difference between the way lizards see and the way human do. Both have two eyes, but the lizard's eyes are on the side of its head and separated by a snout. This arrangement prevents depth perception. In contrast, human eyes are closer together and allow for depth perception. Interdisciplinary approaches allow for, long for, new dimensions of depth and insight. Applied to a dense fact, interdisciplinary approaches "reveal deeper meanings inside themselves, and point outward to other facts, other ideas, other meanings."

Second, Jonathan Z. Smith, in a plenary session recalled his proposal for a University of California curriculum (in the mid 1960s) that would require each student to spend a semester, or maybe a year, pursuing all that could be learned starting from a single sentence. He did not speak of dense facts, but the example he gave from a military report and that he explored surely was like what we intend. And it demonstrated the sort of anti-disciplinary position that Carp took at the end of our day. Smith clearly cared more about learning and knowledge than about sharpening the tools of the discipline as ends in themselves.

At St. Olaf we think of Jim Farrell (see his new book: The Nature of College) as the king of the dense fact, perhaps even as the originator of this approach. In fact, it is an American Studies approach which appears to have been suggested by Gene Wise in 1979. Recently I gained some new perspective on the dense fact approach and disciplinary study when I heard from two remarkable scholars at the 2010 American Academy of Religion meetings in Atlanta.

First: Richard Carp spoke to a workshop on interdisciplinarity. As I've come to expect from him, he brought clarity to the complex matter without over simplification.

Terminology: mutlidisciplinary is like parallel play. Two or more disciplines are in play, but not with each other. I (DeAne) think of this a bit like a meal served in courses. Interdisciplinary requires that two or more disciplines are working together. I suppose this might be like using two chop-sticks rather than a spoon which is set down and then a fork. Transdisciplinary, is applied to a topic or subject of study that requires more than one discipline to consider. Food, in my view, is a fine example of such a topic. A dense fact needs to be such a topic.

Richard also spoke of these matters by analogy to sight, more specifically to the difference between the way lizards see and the way human do. Both have two eyes, but the lizard's eyes are on the side of its head and separated by a snout. This arrangement prevents depth perception. In contrast, human eyes are closer together and allow for depth perception. Interdisciplinary approaches allow for, long for, new dimensions of depth and insight. Applied to a dense fact, interdisciplinary approaches "reveal deeper meanings inside themselves, and point outward to other facts, other ideas, other meanings."

Second, Jonathan Z. Smith, in a plenary session recalled his proposal for a University of California curriculum (in the mid 1960s) that would require each student to spend a semester, or maybe a year, pursuing all that could be learned starting from a single sentence. He did not speak of dense facts, but the example he gave from a military report and that he explored surely was like what we intend. And it demonstrated the sort of anti-disciplinary position that Carp took at the end of our day. Smith clearly cared more about learning and knowledge than about sharpening the tools of the discipline as ends in themselves.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)